The Ministry of Finance (MOF) says that it is currently working with the Ministry of Domestic Trade and Cost of Living (KPDN) and observing how they would be able to readjust the pricing of imported goods, following the continued strengthening of the Ringgit.

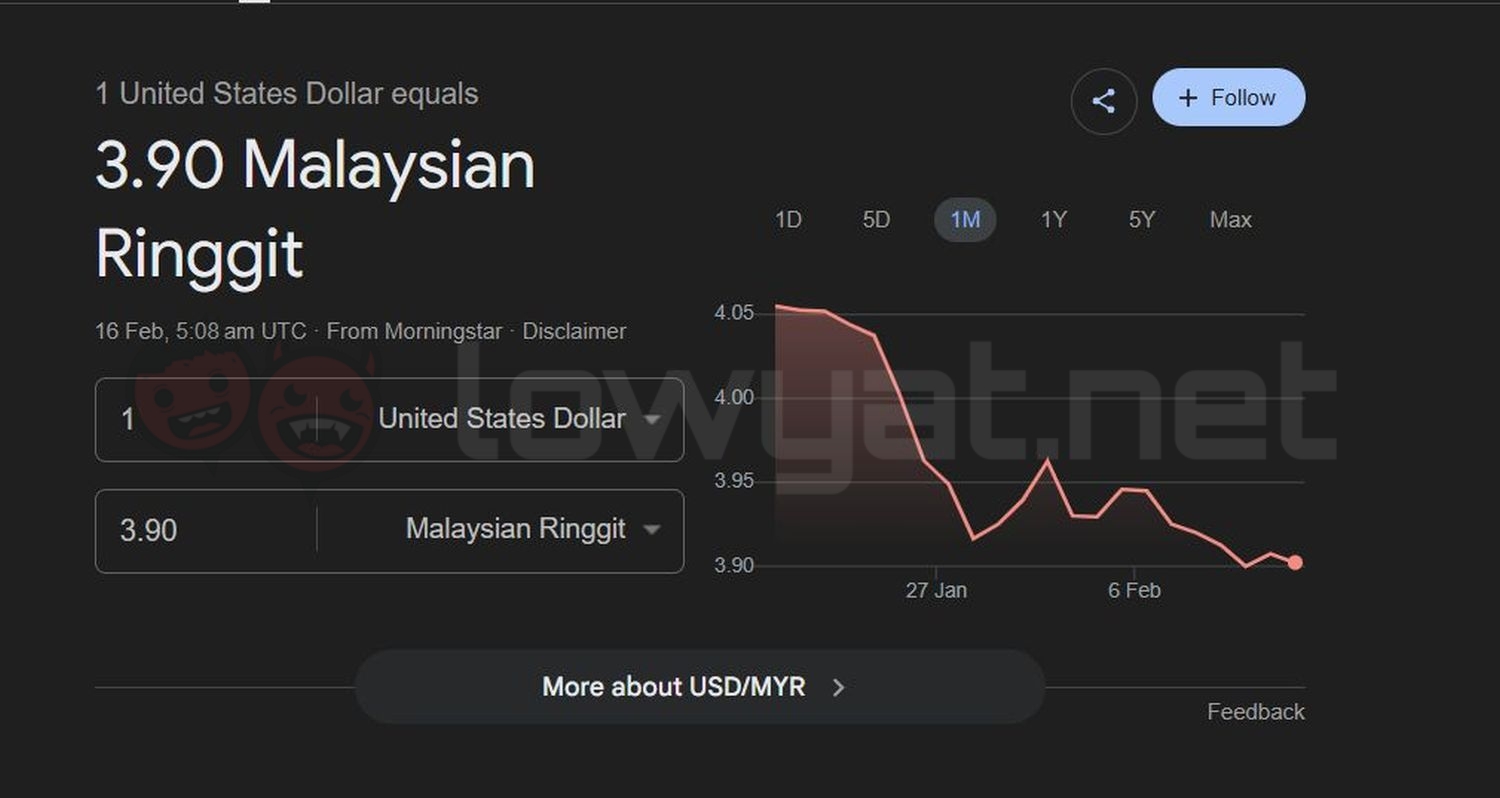

Since early last year, Datuk Seri Amir Hamzah Azizan, Finance Minister II, says that the Ringgit has strengthened 14% on average against the US Dollar. As of this publication, the average value of our currency stands at RM3.90 per US$1.“The rise of the ringgit is good for imported goods, and our current issue is to ensure that importers also ‘pass through the lower cost’ to the people. This is something we are still analysing and working on with KPDN, and we will monitor if there is an opportunity to reduce the prices of imported goods,” Azizan said.

Azizan also said data released by the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) showed that Malaysia’s economy remains resilient, with gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 6.3% in the fourth quarter and 5.2% for the full year last year, among the highest in Asean.

Strong Currency, Strong Problems

While a strong or strengthening currency is a good thing, like everything else in life, having a strong currency can also have consequences and act as a double-edged sword. We all know that a strong Ringgit means stronger purchasing power parity; Malaysians travelling overseas, as an example, won’t feel the pinch quite as hard in countries where their currency is stronger, such as the US, UK, or any country that is a member state of the EU.

Another point in the “Pro” column, and in the case of nation building, is that if there is a foreign debt to be paid back, it also won’t cost as much. Again, as an example, let’s say Malaysia has a foreign debt to the US at US$100 million. If we had, hypothetically speaking, paid off the debt in full in the month January, when our currency was valued at an average of RM4.06, we would have paid RM406 million.

If Malaysia paid that same hypothetical debt off today instead, we’d be paying RM390 million. So yeah, that would’ve basically been RM16 million saved.

But again, those are the plus points. Some of the “Cons”, or the opposite effects of having a strengthening Ringgit, if you prefer, is if you’re an overseas worker or if you’re earning in a foreign currency, you’re earning less than before. Take Singapore as a nearby example: Many Malaysians working in the sovereign nation earn in their currency, which currently stands at an average of RM3.09 per SG$1. Just one month ago, the value of the one Singaporean dollar was worth RM3.17 on average. Some of you obviously would think that a few sens lower isn’t a big deal, but that small difference adds up in the grand scheme of things.

Another potential drawback to having a strong currency is the decline in competitiveness, particularly in manufacturing. Many industries in the West choose to outsource their manufacturing operations to companies in Asia, such as China and Vietnam in Southeast Asia. Mainly keep overhead low, and above all else, it’s cheaper. Of course, this is contingent upon any ongoing geopolitical issues between the relevant countries. While these issues do play a major role in determining the status of a business, it isn’t always or necessarily the governing factor. For example, Apple shifted its entire manufacturing process out of China and opened up factories in India, Vietnam, and Mexico.

And, of course, there’s the potential reduction in tourism. Because the value of the Ringgit is stronger, foreign tourists may begin to feel less inclined to visit our country, as they’d be paying more than they typically did just a year ago.

(Source: The Edge)